The Project to Digitize Manuscripts in Myanmar

By William Pruitt

1. Aims of the Project

A project to digitize palm-leaf manuscripts in Myanmar was begun in February 2013 with the following aims to:

- help preserve Myanmar’s heritage of texts (principally Buddhist texts),

- make photos of texts available for free to scholars all over the world,

- help raise the awareness in Myanmar of the value of manuscripts and early editions of texts,

- train people in Myanmar to care for manuscripts and books and take over the work of digitizing them.

The project has been made possible thanks to funds raised by Professor Yumi Ousaka and Dr Sunao Kasamatsu. The following generous grants have made it possible to make good progress:

- Scientific Research B (SRB) by JSPS (Japan Society for the Promotion of Sciences) from April 2011 to March 2014 (Head Investigator: Ousaka)

- Challenging Exploratory Research (CER) by JSPS from April 2013 to March 2015 (Head Investigator: Kasamatsu)

- KDDI Foundation from April 2013 to March 2015 (Head Investigator: Kasamatsu)

- Mitsubishi Foundation (MF) (Head Investigator: Kasamatsu)

- Scientific Research B (SRB) by JSPS (Japan Society for the Promotion of Sciences) from April 2016 to March 2019 (Head Investigator: Kasamatsu)

- Chuo Academic Research Institute (CARI) of Rissho Kosei-kai (2017) (Head Investigator: Dr William Pruitt of the PTS. Associate Director Dr Yasutomo Nishi of CARI was very helpful in obtaining this funding.

The project is also supported by the Pali Text Society. The photographs and scans will all be the property of the Pali Text Society. Further help comes from the University of Toronto, Canada, where this site has been developed.

2. Inspiration from Similar Projects

It is difficult to keep up with the resources available on the internet for Burmese manuscripts and books as well as manuscripts and books of Pāli texts from other countries. There are many similar projects like ours, both past and present. When we began to work on the project to digitize manuscripts in Myanmar, we were hoping to emulate a Web site for Laotian palm-leaf manuscripts: http://www.laomanuscripts.net. The images on this site are in black and white, which seemed a good idea as it could mean keeping down the size of the files. In practice, however, we soon found that the dark colour of the palm leaves did not offer enough contrast with the letters to turn colour photos into black-and-white files. We later learned that the Laotian site was able to use black-and-white photos because the images were scanned from microfilms made before the days of digital cameras. As computer memory has become less and less expensive, the need to reduce the size of the files is not as urgent as before.

Two other sites that serves as an example are hosted by the École française d’Extrême-Orient, One is for manuscripts using Khmer script: http://www.khmermanuscripts.org. The images on this site are in colour and can be enlarged by scrolling over the window with the text. We have not been able to learn more about the computer program used for this site. The other is a site for Lanna manuscripts (“A northern Thailand collection of chronicles and others texts”): http://www.efeo.fr/lanna_manuscripts/manuscript/list.

PDFs of manuscripts in Sinhalese script can be found on a Web site hosted by the Palm Leaf Manuscript Study and Research Library, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Kelaniya in Sri Lanka:

http://www.kln.ac.lk/socialsciences/units/plmsrlJ/index.php/collection/palm-leaf-digital-collation.

3. The Material Currently Available for Our Project

Our project is different from the ones just mentioned as we are concentrating on photographing and scanning entire collections of manuscripts which will be useful for scholars preparing critical editions of texts. We include a greater variety of types of texts as well. In addition to texts in Pāli, we include Burmese nissaya (Pāli texts with Burmese and Mon word-by-word translations and explanations), texts in Burmese and Mon, and illustrated manuscripts. Scans of early Pāli editions printed in Burma that are difficult to find will also be of great value to scholars. The photographs and scans will be made available as PDFs and can be used as E-books.

4. Computer Programs Developed for Our Project

Dr Win Htay, who is the director of the computer university in Thaton, is developing a computer program to automatically crop the photos and put them in PDFs. We will be able to offer this program free of charge to scholars. Dr Kazuhiko Fujiwara, Professor Miyao, and Professor Yumi Ousaka of the National Institute of Technology, Sendai College, are now making a computer program to compile an electronic book from photos of the palm-leaf manuscripts together with information about the leaves that is automatically added to the book — for example its serial number and the front and backs of the leaves (recto and verso). This computer program will save a great deal of time and can easily process hundreds of manuscripts, each of which contains dozens of palm leaves. We can edit these books, depending on how they will be used — for example, to upload them to a Web site in order to preserve the manuscripts in a very clear formate so that they can be studied in the future.

5. Manuscripts of Artistic Interest

The first library whose manuscripts are being digitized possesses several illustrated parabaiks (accordion-style books on heavy paper)[2] with subjects such as the Thirty-one Planes of Existence, medicinal plants, and royal regalia. These have already proven to be of interest to scholars working on Burmese art. Another type of manuscript used in Burma are Kammavācās which have texts used for ordination ceremonies and other acts of the Saṅgha. Formerly, these could be very elaborate manuscripts with a special script that monks would not be able to read now. Today, printed versions with modern Burmese script are used. The U Pho Thi Library has a rare late Kammavācā manuscript that uses modern script; it was made in 1951 in Mandalay in honour of U Pho Thi after his death. It is housed in an ornate chest. Photos of the Kammavācā manuscripts are being used by Ms Sinead Ward for her doctoral thesis.

Ornate manuscript cabinet

6. Cataloguing Manuscripts

Both of the monastery collections that we have been given permission to photograph and scan have been more or less well catalogues. A catalogue has been published of the manuscripts in the Thar-Lay Monastery on Inle Lake: U Thaw Kaung, U Nyunt Maung et al., Palm-leaf Manuscript Catalogue of Thar-Lay (South) Monastery.[3] In the introduction, U Thaw Kaung says that this is the first such catalogue prepared in Myanmar. When we made our initial trip to the monastery, we were shown a typed list of manuscripts in a nearby monastery, the Nga Phe Kyaung (known as the jumping cat monastery). We went to see if those manuscripts could also be photographed, but we were informed that they had all been given away.

There are several lists of the manuscripts in the U Pho Thi collection in Thaton. Three different sets of numbers were used over the years. None of them is up to date, however, so it will be necessary to prepare a details catalogue once the manuscripts have been photographed. One list was prepared fairly recently by U Nyunt Maung and a group of librarians from Yangon. In 1998, ten scholars from the Universities’ Central Library, Yangon, worked in the library for ten days and made a list of 775 manuscripts. But they were not able to prepare a complete catalogue. With the photos, we will be able to check the accuracy of the earlier lists and add more detail. We hope to prepare a catalogue similar to the one of Burmese manuscripts in the Library of the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine in London.[4] In the meantime, we have published a provisional catalogue.[5]

7. How Two Collections Were Selected

There are many challenges to a project such as ours. State controlled institutions in Myanmar are generally off limits for anyone coming from outside the country. These include universities, museums, and religious monuments like the Shwedagon Pagoda. Many areas in Myanmar are off limits to foreigners, so only Burmese nationals will be able to photograph manuscripts in those areas. For the time being, we are concentrating on collections we can work on ourselves.

There is also the problem of explaining the importance of preserving and making available manuscripts and earlier editions of books. Many monks and Burmese scholars think that once a text has been printed, only the edition needs to be consulted. When I asked an 84-year-old monk if he had ever used a palm-leaf manuscript in his studies, he said he had only ever used printed texts. He had given most of the manuscripts in his monastery to a museum in Yangon. Four manuscripts are still with him, and he agreed to let us photograph them before giving them to the same museum.

There is some validity in the idea that it is not necessary to consult every available copy of a text in preparing a critical edition. Many copies are very derivative and do not include early readings. As the librarian U Nyunt Maung told me, so many manuscripts of the Dīgha-nikāya are given to the Shwedagon Pagoda library, they are not catalogued in detail. We even found one manuscript in the U Pho Thi Library that was copied from a printed edition.[6]

Documents that are accessible are found in monasteries, where the head Sayadaw is responsible for the manuscripts and books in the monastery. The original plan was to concentrate on rare texts in Pāli that will be important for revising editions already printed and to edit texts that have not been published. We wanted to identify texts that were copied before around 1860 (that is to say, before the Fifth Council held in Mandalay).[7] The head Sayadaws at the monasteries where we have been given permission to take photographs want us to photograph all their manuscripts, however, so in addition to including nissayas and texts in Burmese and Mon, we now include illustrated parabaiks and scans of selected books printed before the Sixth Council.

8. The Importance of Digitizing Texts

Photographing and scanning manuscripts and books is a very useful way to preserve various versions of texts and the most practical way to make them available. Recent developments in digital photograph, availability of reasonably priced scanners, and computer programs as well as the internet make it possible to digitize texts and make them freely available. Before, it was very expensive to make microfilms, assuming it was possible to take the equipment to where the texts were kept or bring the documents to an institution with the equipment. In some ways, it is easier to get permission to digitize texts in a monastery in Myanmar than to do the same thing in a Western library.

It is rare to find Burmese manuscripts older than 1600. Palm-leaf manuscripts continued to be produced well into the twentieth century, but manuscripts in Pāli from before around 1860 are the most important ones for projects like ours — with the exception of later mansucripts of texts in Burmese that are of interest to historians as well as very rare Pāli texts. For example, the Pali Text Society has published the “old” sub-commentary on the Aṅguttara-nikāya that was found in a Burmese manuscript and edited by the late Dr Primoz Pecenko.[8]

We were able to identify a number of manuscripts in the collections we have begun to digitize that could be edited or used for revised editions of texts. Examples of manuscripts that it would be useful to have digitized found in the Thar-Lay Monastery include manuscripts that can be used when preparing new editions of texts already published in roman script such as the Sammohavinodanī (a.d. 1741), the Petavatthu-aṭṭhakathā (a.d. 1757), the Aṭṭhasālinī (a.d. 1778), the Jinālaṅkāra (a.d. 1773) and the commentary on it, the Jinālaṅkāra-ṭīkā (a.d. 1773). Perhaps more important are manuscripts of texts that have not been edited in roman script such as the Vinayālaṅkāra-ṭīkā (a.d. 1769), the Dhātukathā-anuvaṇṇanā (a.d. 1775), and the Paṭisambhidāmagga-aṭṭhakathā (a.d. 1779).

U Nyunt Maung identified approximately fifty manuscripts in the U Pho Thi Library that contain rare Pāli texts, most of which have not been published. There are also many manuscripts with nissayas, which are word-by-word translations of Pāli texts into Burmese. Many of these could be useful to Burmese scholars.

Another reason it is important to digitize texts is that so many of them disappear. As they are not considered important, monasteries and institutions do not always take care of manuscripts and books. Insect or rodent damage and climate conditions can mean that texts deteriorate and are no longer useful. Texts can be given away by monks who do not consider them important as we discovered at a monastery in Inle Lake. Texts can also be stolen. Many manuscripts were smuggled out of the country and sold in Thailand. The Fragile Palm Leaves Foundation has bought up thousands of these texts and preserved them in Bangkok.[9] For detailed information concerning a very similar situation in Sri Lanka, see Ñāṇatusita, Bhikkhu, “Pali Manuscripts of Sri Lanka”.[10] His article gives a good idea of the number of Burmese manuscripts in monasteries and libraries in Sri Lanka and the urgent need to preserve and digitize them.

In some ways it is more important to scan books than to photograph manuscripts as the poor quality paper and the storage conditions mean that the books rapidly deteriorate. The paper becomes so fragile it crumbles when pages are turned. And insect damage is much more extensive for paper than palm leaves.

9. The First Collections to Be Digitized

Dr Sunao Kasamatsu and Dr Yutaka Kawasaki from Japan and Aleix Ruiz Falqués joined me in photographing manuscripts in large libraries in two monasteries — one in Thaton and one in Inle Lake — in February 2013. We were helped by U Aung Moe Oo. Each of us used the digital cameras we owned which gave uneven results.

We went to two monasteries where we had obtained permission to take photos and make scans: the Thar-Lay Monastery in Inle Lake and the U Pho Thi Library in the Sadhammajotika Monastery in Thaton. The catalogue of the Thar-Lay collection says that there are 886 manuscripts in the collection containing 958 texts. Some 45 manuscripts with texts in Pāli date between 1676 and 1800. The head Sayadaw was away when we went to the Thar-Lay Monastery, and we learned that the keys to the cabinets with the manuscripts had gone missing. Ven. U Sumano, the monk we had contacted beforehand, cheerfully agree to have a locksmith come change the locks. Now there are three sets of keys, so in future it should be possible to consult the manuscripts. The monk did all he could to help us with finding manuscripts, oiling them, and taking photos.

The collection of texts in the U Pho Thi Library is in Thaton, one of the cities in Myanmar where monks go to prepare for examinations, and the Sadhammajotika Monastery is the largest centre where they study. A wealthy layman named U Pho Thi donated the library that bears his name in the early twentieth century in order to aid the monks in their studies.

The U Pho Thi Library building

The library has some 775 palm-leaf manuscripts; the exact figure will only be known once they have all be photographed as some manuscripts are missing.

Ornate manuscript cabinet

A local group of lay people in Thaton support the library. U Kyaw Hlaing, the President of the Suyaṅgabhūmi Pariyatti Sāsanhita Trust, explained that the library was founded in 1923 by a professor of Burmese literature, U Kyaw Tun, and a wealthy layman, U Pho Thi. The Trust’s main work is organizing Pāli exams. They provide lodging and food for monks and novices who come to take the exams, and they organize the ceremony to announce the results.

10. Preparing and Conserving Manuscripts

The members of the Trust had not worked with the manuscripts because they were afraid they would not handle them correctly. Many of them are very enthusiastic about caring for the manuscripts and photographing them, so much so that they bought our equipment from us (computer, camera, and lights) in order to continue taking photographs on their own. Thanks to U Nyunt Maung, the Trust members are now able to take care of the manuscripts efficiently. U Nyunt Maung was an Assistant Librarian at the Universities’ Central Library, Yangon, and is a consultant to the Universities Historical Research Centre. He is still active after retiring from his job as a librarian.

U Nyunt Maung showed the helpers how to use lemon grass oil with powdered carbon to oil the leaves. The oil helps preserve the leaves so they do not turn too brittle and protects them from insects. The powdered carbon stays in the letters that are incised into the leaves with a metal stylus and makes the text stand out. It is important to always rub the leaves in only one direction as rubbing back and forth can result in broken leaves. At one point, when we ran out of lemon grass oil, we used mineral oil with camphor dissolved in it. This is a technique I learned from the conservation department of the oriental manuscript section of the British Library many years ago.

Instructing the helpers

U Nyunt Maung also taught the helpers how to put the leaves in order. The numbering system for manuscripts uses consonants and twelve vowels, each set being called an aṅga (for example, ka, kā, ki, kī, ku, kū, ke, kè, ko, kō, kaṃ, kā:). Each consonant is combined with the vowels, and if they are all used up, a system of double consonants is used. The scribes did not always number correctly, however, so there are a number of manuscripts where there can be two leaves with the same number (usually made clear by adding the Burmese numbers 1 and 2 after the consonant with vowel). Texts might be moved from one manuscript to another and renumbered, the original numbers crossed out or cancelled using a small circle and the new numbers written beside the old ones. There were a few cases where leaves were put back in the wrong manuscript. As titles are usually included in the right-hand margins of the leaves, it is often possible to put the leaves back in the correct manuscript.

Wrapped manuscripts

U Nyunt Maung also instructed the members of the Trust about the cloth covers for the manuscripts and the ribbons with text woven into them used to tie up the manuscripts.[11] U Ye Kyi from the Yangon Universities’ Central Library assisted U Nyunt Maung and helped with taking the photos. He checked the manuscripts to insure that the leaves were in order and helped turn the leaves for the photographs. He is also expert in wrapping the manuscripts.

Palm-leaf manuscript with woven ribbon used to tie the manuscript

The Trust is now reorganizing the manuscripts, adding teak wood covers and cloth wrappers to those that were bare palm leaves. They are also reshelving the printed books. They plan to have the manuscripts oiled at regular intervals of approximately ten years.

Work on photographing the manuscripts went much faster thanks to the division of labour. The people taking the photos did not have to prepare the palm leaves or rewrap the manuscripts when the work was done. This saved a considerable amount of time. Over the years the manuscripts were not kept in order, so finding a specific text could be very time consuming. Now, the manuscripts are all in order. The Trust is very happy to have a set of photos as this will mean that when people want to consult a text, they can use the photos rather than the actual manuscript. So there is less chance that the order will be disturbed, that the manuscripts will be mishandled, or that manuscripts will go missing.

11. Photographing and Scanning Texts

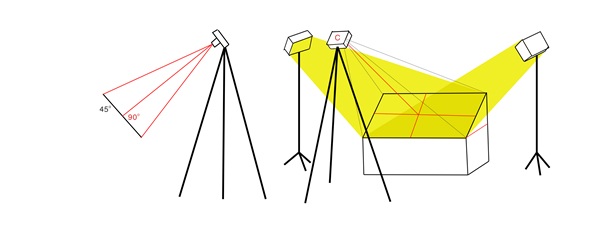

Markus Wörgötter, a professional photographer, gave us valuable information about the equipment to use and how to set up a camera, computer, and easel to take photos. It is important to use a camera with the proper lens as palm-leaf manuscripts are very wide so it is essential that the edges and corners are kept in focus. Mr Wörgötter suggested we use a reflex-camera with around 10 million pixels, with a fixed focal lens of 50–70 mm. Using ISO 100 or 200 is acceptable, but ISO 400 should be avoided as it will produce grainy images and reduce the quality of the picture. He suggested using a colour-pad and small grey card to make it possible to adjust the colour balance when editing images. We found this was mainly important for illustrated parabaiks, but not essential for palm-leaf manuscripts where the main concern is the legibility of the text. We purchased the camera he suggested (Canon Eos 1100D) and used the diagram he sent (see below) as a guide when setting up the easel for the manuscript, the studio lights, and the tripod with the camera at the correct angle.

The computer program that came with the camera (Canon EOS Utility) meant we were able to connect the camera directly to the computer, see the images on the screen, and adjust the focus and other settings before taking photos. The photos could be checked immediately. We took raw data and JPEG images. The raw data photos will mainly be important if photos need to be edited. Again, this would mainly be the case for manuscripts with colour illustrations. It did prove to be necessary to double check all the photos to be sure there were no mistakes such as a hand in the way. To facilitate the use of computer programs, we now use a solid background for the leaves. We started with black cloth, but now use bright green to make it easier for a computer program to automatically crop the images of the leaves in the photos.

The easel and lights

We use a Fujitsu ScanSnap SV600 for scanning books. The program that comes with the scanner will take care of cropping, correct curved page distortion, and save documents in PDFs. The resolution was not high enough to use for palm-leaf manuscripts, however.

The computer and camera

12. Accomplishing Our Objectives

We are well on the way to fulfilling our mission. We should soon have all the manuscripts in the U Pho Thi library photographed and a good number of printed texts scanned. As the files will be copied and kept in several locations, they will be well preserved and easily available. As can be seen from the list in the Appendix, a number of scholars around the world have already benefitted from our project.

The group responsible for the U Pho Thi Library are now in a position to care for their collection. Our help has raised their awareness of the value of what is there. An article in a Burmese newspaper about our project in Thaton resulted in people coming to see the magnificent room housing the collection, including the gilded cabinets with small statues of devas and a gilded ceiling with inlaid glass ornaments. Publicity about the library has also brought in donations. A Mon monk who is working to preserve the Mon language and Mon texts visited the library and was so impressed with the project that he made a donation.

We were especially happy that the U Pho Thi Library group were able to buy our equipment and continue taking photos when we were not there.